This week we learnt some of the things that separate assembly language from machine code in the context of AVR (or should I say AVR Studio).

Important Note 1: Assembly Language

In AVR assembly an input line takes the form of one of these, ([foo] = Optional)

[label:] directive [operands] [Comment]

[label:] instruction [operands] [Comment]

Comment

Empty Line

where a comment has form,

; [Text]

Important Note 2: Pseudo Instructions

AVR Assembly (using AVR studio) has some additional commands that are not part of the AVR instruction set, but the assembler (that is part of AVR studio) interprets into machine code.

Pseudo instructions are recognised by their preceding '.' (dot character). eg,

.equ CONST = 31

, will upon assembly go through the code and replace CONST with 31.

Here are the AVR assembly Pseudo Instructions.

| Directive |

Description |

| BYTE |

Reserve byte to a variable |

| CSEG |

Code Segment |

| CSEGSIZE |

Program memory size |

| DB |

Define constant byte(s) |

| DEF |

Define a symbolic name on a register |

| DEVICE |

Define which device to assemble for |

| DSEG |

Data Segment |

| DW |

Define Constant word(s) |

| ENDM, ENDMACRO |

End macro |

| EQU |

Set a symbol equal to an expression |

| ESEG |

EEPROM Segment |

| EXIT |

Exit from file |

| INCLUDE |

Read source from another file |

| LIST |

Turn listfile generation on |

| LISTMAC |

Turn Macro expansion in list file on |

| MACRO |

Begin macro |

| NOLIST |

Turn listfile generation off |

| ORG |

Set program origin |

| SET |

Set a symbol to an expression |

.byte - Reserve some space (only allowed in dseg). eg.

.dseg

var1: .byte 4 ;reserve 4 bytes and store address in var1

.CSEG

ldi r30, low(var1) ; Load address into Z low register

ldi r31, high(var1) ; Load address into Z high register

ld r1, Z ; Load VAR1 into register 1

...and some more...

.def FOO=r30 ;give register 30 the symbolic name FOO

.equ var = 2 ;like C's #define statement

.set var = 2 ;like a global variable in C

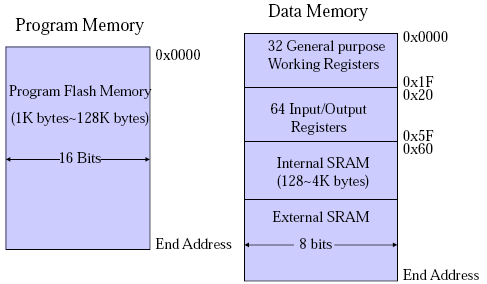

Important Note 3: Segments

There AVR three segments of an AVR assembly program. Also when writing an assembly program you need to be able to specify which segment you are referring to, so you need to declare this using an AVR assembler directive shown in brackets below.

- Code Segment (.cseg)

- Data Segment (.dseg)

- EEPROM Segment (.eseg)

"The CSEG directive defines the start of a Code Segment. An Assembler file can consist of several Code Segments, which are concatenated into one Code Segment when assembled. The BYTE directive can not be used within a Code Segment. The default segment type is Code. The Code Segments have their own location counter which is a word counter. The ORG directive can be used to place code and constants at specific locations in the Program memory. The directive does not take any parameters." [1]

Notes from the Lab

Assembly Code and Machine Code

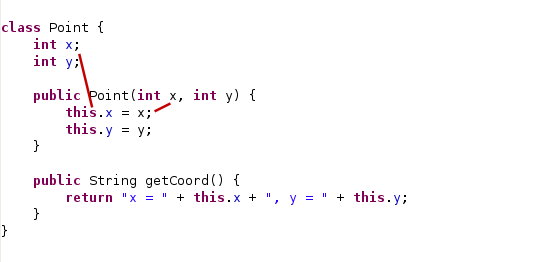

In the lab we looked at this AVR assembly program,

.include "m64def.inc"

.def a =r16 ; define a to be register r16

.def b =r17

.def c =r18

.def d =r19

.def e =r20

main: ; main is a label

ldi a, 10 ; load 10 into r16

ldi b, -20

mov c, a ; copy the value of r16 into r18

add c, b ; add r18 and r17 and store the result in r18

mov d, a

sub d, b ; subtract r17 from r19 and store the result in r19

lsl c ; refer to AVR Instruction Set for the semantics of

asr d ; lsl and asr

mov e, c

add e, d

loop:

inc r21 ; increase the value of r21 by 1

rjmp loop ; jump to loop

The machine code executable produced by AVR studio was 24 bytes long, the question was why. It's actually quite simple, all of the here instructions are 1 word (2 bytes = 16 bits), there are 12 instruction so total 24 bytes. One thing that initially confused me was the weird encoding. Back in 1917 I got the impression that if you have something like mov r16 r17 that this would be represented in machine code as some number for the mov operation followed by two more numbers of the same bit size for the registers. However this can vary depending on the architecture.

For example the mov operation, MOV Rd, Rr has encoding 0010 11rd dddd rrrr. The instruction takes up 6 bits, the source register takes up 5 bits and the destination takes up 5 bits (total 16 bits). The reason that the source and destination bits are intertwined is that it makes things easier on the hardware implementation to do it this way.

The program above has machine code (in hexadecimal),

E00A EE1C 2F20 0F21 2F30 1B31 0F22 9535 2F42 0F43 5993 CFFE

and annotated,

+00000000: E00A LDI R16,0x0A Load immediate

+00000001: EE1C LDI R17,0xEC Load immediate

+00000002: 2F20 MOV R18,R16 Copy register

+00000003: 0F21 ADD R18,R17 Add without carry

+00000004: 2F30 MOV R19,R16 Copy register

+00000005: 1B31 SUB R19,R17 Subtract without carry

+00000006: 0F22 LSL R18 Logical Shift Left

+00000007: 9535 ASR R19 Arithmetic shift right

+00000008: 2F42 MOV R20,R18 Copy register

+00000009: 0F43 ADD R20,R19 Add without carry

+0000000A: 9553 INC R21 Increment

+0000000B: CFFE RJMP PC-0x0001 Relative jump

Status Register

Stepping through this program also shows a few of the status registers in use. The Status register, like all the other registers has 8 bits, namely,

| SREG |

Status Register |

| C |

Carry Flag |

| Z |

Zero Flag |

| N |

Negative Flag |

| V |

Two’s complement overflow indicator |

| S |

N ⊕ V, For signed tests |

| H |

Half Carry Flag |

| T |

Transfer bit used by BLD and BST instructions |

| I |

Global Interrupt Enable/Disable Flag |

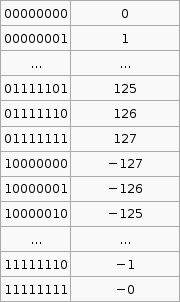

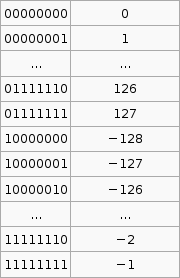

Last week we saw how signed and unsigned numbers are stored, so if you look at the program above you will see that the last part just increments a register infinitely over and over. Stepping through this shows us what the status register does as we do this. Remember that AVR does all arithmetic in two's compliment.

| 0 |

H Z |

| 1-127 |

H |

| 128 |

H V N |

| 129-255 |

H S N |

As you can see the values that are negative under the two's complement 128-255 have the N (negative) flag. Also from 127 then to 128 under two's compliment we have gone from 127 to -128, so the V (Two’s complement overflow indicator) flag is indicated. 0 has the zero flag.

The Rest

The lecture notes go over some of the AVR instructions but I think the docs provided by Atmel are fine. What I do think needs explaining (and me learning) is the carry flag and the difference between operations like add without carry (ADD) and add with carry (ADC).

Here is how I understand the carry bit. Say we have 4 bit registers and try to add (in binary) 1000 and 1000, the answer is 10000 however this is 5 bits and we only have 4 bits available to store the result. An overflow has occurred. To introduce some terminology, the most significant bit (or byte) (msb) is the left most bit (or byte) in big-endian (right most in little-endian), and vice-versa for least significant bit (or byte) (lsb). The carry bit (C flag) is the carry from the msb. This can indicate overflow in some cases but not always, it those cases the V flag (Two’s complement overflow indicator) is set.

So getting back to ADD and ADC, ADD will just add the two numbers ignoring the carry bit and ignoring overflow whereas ADC will actually add the carry bit to the result. At least this is what I've observed, though I'm not 100% sure on this.

References

[1] AVR Assembler User Guide. www.atmel.com/atmel/acrobat/doc1022.pdf

Bibliography

AVR Assembler User Guide. www.atmel.com/atmel/acrobat/doc1022.pdf

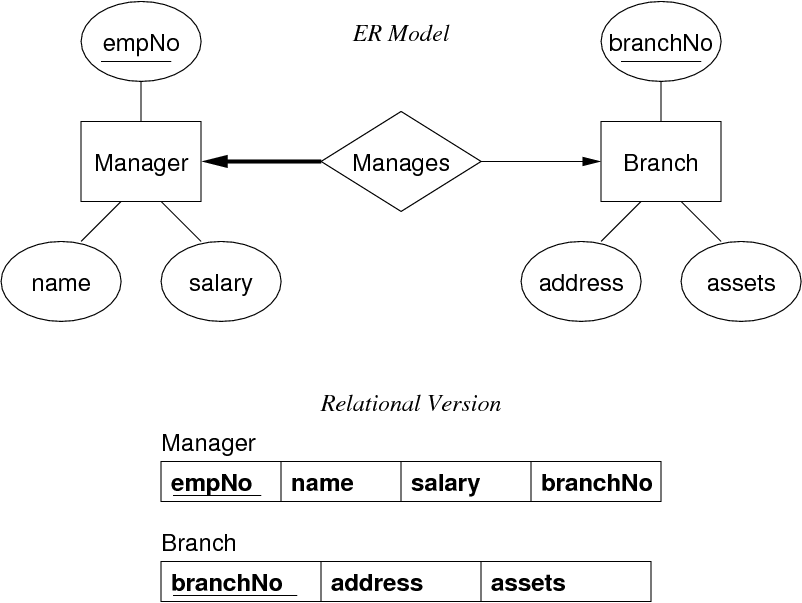

Mapping 1:1 Relations

Mapping 1:1 Relations