I began wondering about this mainly when the idea of a basis is used in linear algebra, although it seems to be strongly related to scalars, just as basis is to vector as one is to scalar.

This area of investigation for me arose when then they took coordinate vectors out of the UNSW MATH1231 (2007) syllabus. So I had to do a bit of reading on my own. To understand coordinate vectors its helpful to look at the vector space of polynomials. For example take the polynomial 3 - 2x + x2. Now if we put the coefficients into a vector, (3, -2, 1) then this vector is called the coordinate vector of 3 - 2x + x2 with respect to the ordered basis {1, x, x2}[1]. This sounds clear, but let me propose the following.

Say we have the coordinate vector (1,2,3) with respect the the ordered basis S = {(1,0,0), (0,1,0), (0,0,1)}, denoted [(1,2,3)]S. How is this different to just (1,2,3)? Aren't all vectors, by convention defined with respect to the standard basis of that vector space? But that cannot possibly make sense because bases are defined in terms of vectors, so that would be a recursive definition which is not logically valid. There must be a more reasonably explanation.

Now looking at this in the vector space of say $latex \mathbb{R}^2$ we can take one basis of B = {(1,0), (0,1)} which is the standard basis, and another C = {(1,1), (-1,1)}.

Now if we define the point (1,2) with respect the the basis C, then with respect to the basis B this is the point, 1(1, 1) + 2(-1, 1) = (-1, 3). So essentially this allows us to still work with respect to the standard basis B, but we can work in the frame of C which allows us to then say treat the point (1,1) as just (1,0) which can simplify things.

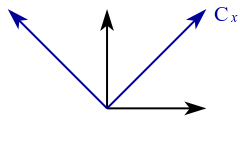

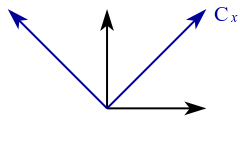

Again looking at this graphically say in $latex \mathbb{R}^2$ then we can just draw essentially any two non-parallel lines which we call our axis or basis. Any mathematics that is done in any of these coordinate systems with respect to that coordinate system (i.e. the two lines drawn) would be the same. (1,1) + (2,0) would give (3,1) in both systems. Its only when we start defining one vector in one system with respect to the basis of the other system that we need to worry about the difference between the bases.

In the same sense I would say, mathematically it is meaningless to draw some Euclidean geometry on paper without drawing in your standard basis. Without them everything is meaningless as you define vectors as coordinate vectors with respect to some basis. Just as the polynomial 3 - 2x + x2 is really just the vector (3, -2, 1) with a standard basis of {1, x, x2}. I guess you would call them metrics of the vector space of $latex \mathbb{R}^2$, just like 1 is the metric of all subsets of the real numbers (is it?).

As a final note I think this is just the same as 2 is really means 2 × 1, and 3 means three lots of 1's. Any links to abstract algebra? Probably, I'm not sure.

References:

[1] MATH1231 Algebra [Online]. Angell D. 2005. Accessed July 2008. Ch 6, Pg 70. http://web.maths.unsw.edu.au/~angell/1231alg/