Part II of Stephen Cohen's lecture, (audio here) (2008 lecture slides here). Just as a side note, I think I've picked up more by listening to the audio where I can stop it to think about what was said, that I have by going to the lecture. Also it seems that the content in the two lecture doesn't fall under the title really well. It seems some of the stuff from lecture one falls under lecture two's title, and some of the stuff from lecture two falls under lecture ones title.

Cohen started by talking about some ethical theories. Here is a diagram based on the one we were shown.

On the left we have the group of ethical theories, consequential, that is based on the view that "Acts are right based on their consequences." Under this umbrella there are four different views as shown.

- Egoism - “An act is right insofar as it advances my welfare.” Although nowadays people tend to contrast this with thinking about ethics.

- Utilitarianism - "Acts are right insofar they produce happiness and they are wrong insofar as they don't produce happiness." The wrong way to thing about utilitarianism would be "the greatest good, for the greatest number", rather it is about maximising happiness not distributing the most. For example if I had $100 to distribute to 50 people, it may well be that giving the whole $100 to one person would produce greater happiness than the sum of happiness of 50 people each getting $2. If this were so than the utilitarian view would be to give the whole $100 to that one person.

- Nationalism - Acts are right if they are in the best interest of the nation as a whole.

- Epistemism - "Acts are right insofar as they advance our knowledge, and they are wrong if they don't do that."

On the right we have another view where ethics is based on non-consequential things. That is, to determine if an act is right or wrong it in fact has nothing to do with the consequences of the act. Instead it has to do with other things such as rights, duties, contracts, fairness, etc.

Or to put it as Ken Robinson and Achim Hoffman have it in their introduction article,

- Deontological in which the reasoning is based on axioms or laws, for example, “You shall not lie”

- Teleological in which the reasoning is based on outcomes.

Kant was a non-consequential thinker. His idea (how I have interpreted it) was that good will is what makes an act right, where good will is recognising your duty and then being able to make yourself do it (eg. you crash into a parked car you realise it is your duty to leave your details and then your able to make yourself to do that, even if you don't want to do it).

Cohen then goes on to make a very good point about autonomy. The audio segment is embedded here, (or direct download)

[audio http://www.cse.unsw.edu.au/~amha119/se4921-090317-autonomy_cut.mp3]

"Kant was the person, and this has been a feature of thinking about ethics ever since Kant. A number of people think that a really important feature about ethical performance is autonomy, autonomy. Which means being free from various kinds of constraints and being able to generate something all on your own. Autonomy, I do it not because I have to, not because I've been trained to do it. In that respect you see you could be free ...--go do whatever you want, but you've now been as it were brainwashed to do a certain kind of thing--. You would be free but you wouldn't be autonomous. Autonomous is being able to come up with the principle, to generate it yourself and then make yourself do it. And that has been a very important element in thinking about ethics." --Stephen Cohen, 2009.

Aristotle on the other hand thinks ethics is about having the right character. Imagine there's person walking along a pier and he sees someone who's drowning. The person with a good character (a good kind of person) does think twice, they pick up the lifefloat tube and trow it to them. This person has good ethical values as a result of their good character. Taking another approach, same situation but now someone who doesn't have good character who doesn't value human life. They don't want to save this person, but they know that they ought to save them so they throw them the lifefloat to save them, despite the person not wanting to do it. This person does not have good character, but they have good ethical vales because they recognised what they ought to do, and they did it. This is Kant's view.

Another view, sometimes called contractarism, focuses on "Keeping the terms of the contract."

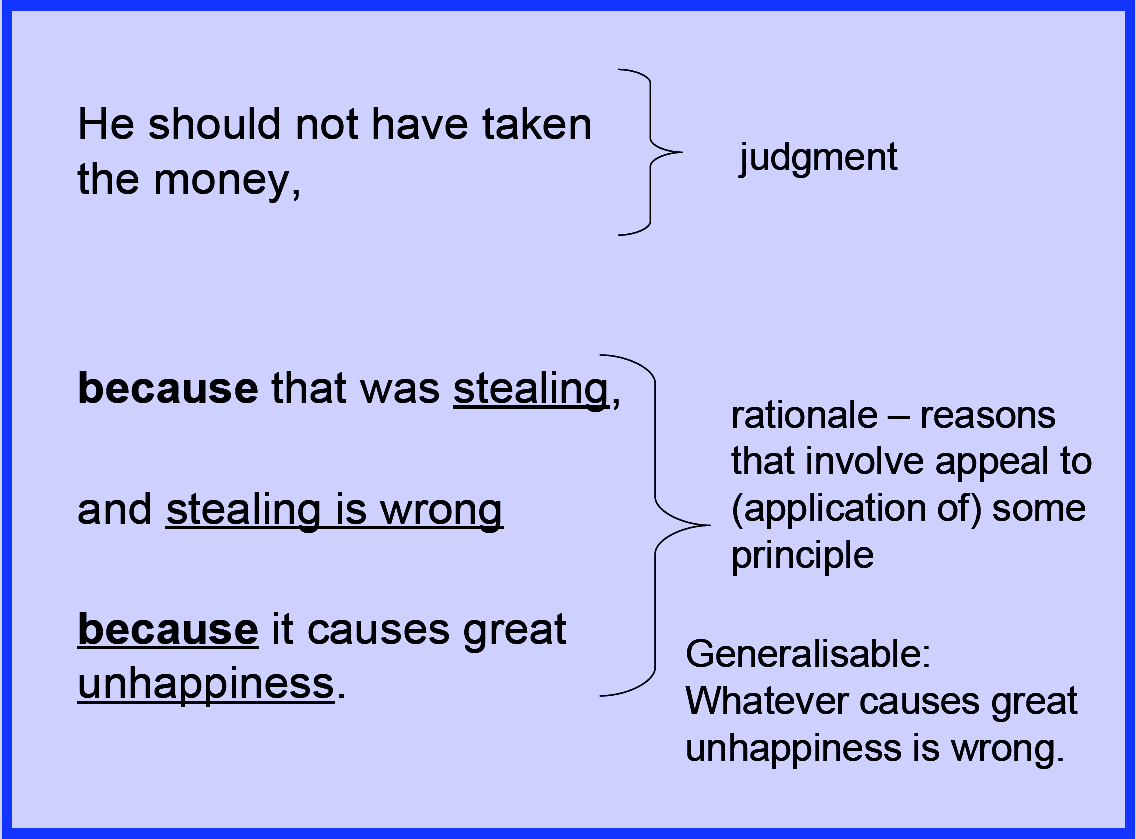

Another slide that Cohen showed was this.

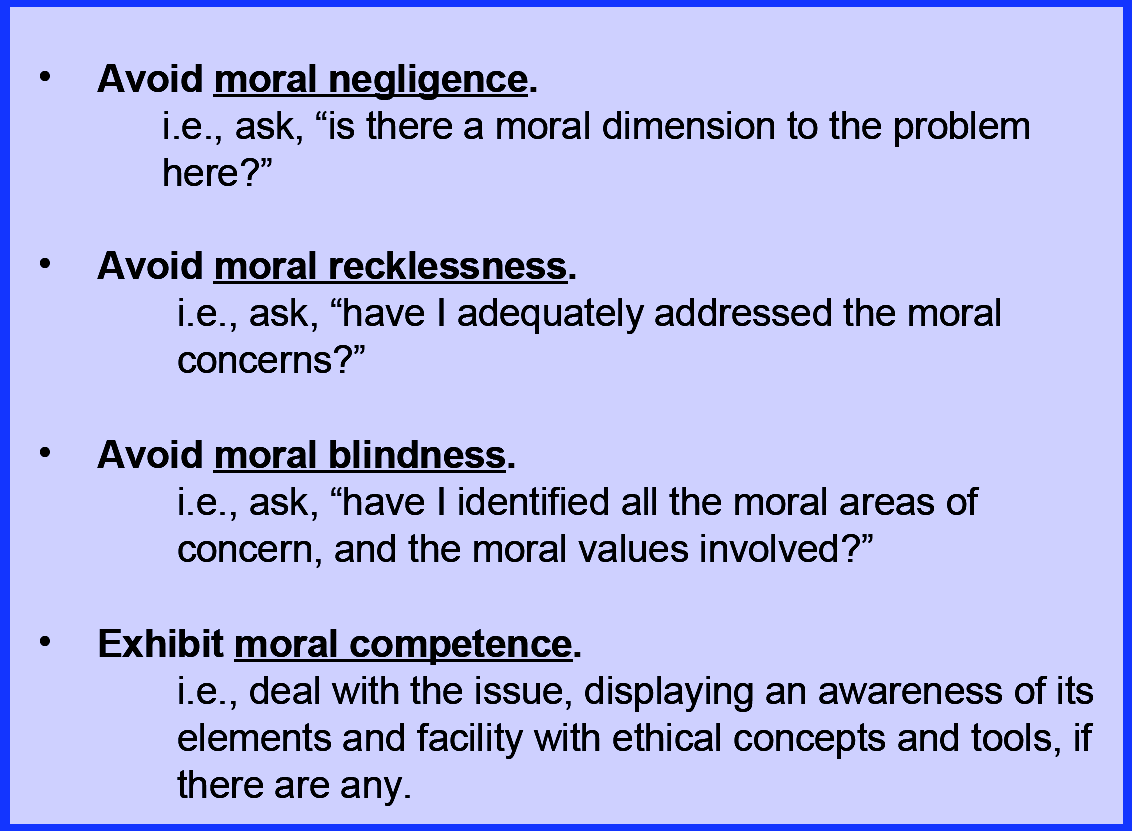

Cohen makes the point that in order to have made a moral judgement you need to make a judgement, have some justification for that judgement, and also have some principle that lead you to believe that that justification was right.

judgement > justification > principle

If you don't have this, you don't have a moral judgement. He also says that the way you could discover that something is not a moral judgement, rather you have some bias or preference towards that judgement and it is not a moral judgement is if you don't have that, you don't have judgement > justification > principle.

If you are more committed to a particular judgement rather than the principle. Cohen then goes on to say that he thinks this is how we go on about moral reasoning. We try to put these two together. Sometimes we modify the judgement in light of the principle, and sometimes we modify the the principle in light of the judgement. These are exceptions to the rule (or the principle).

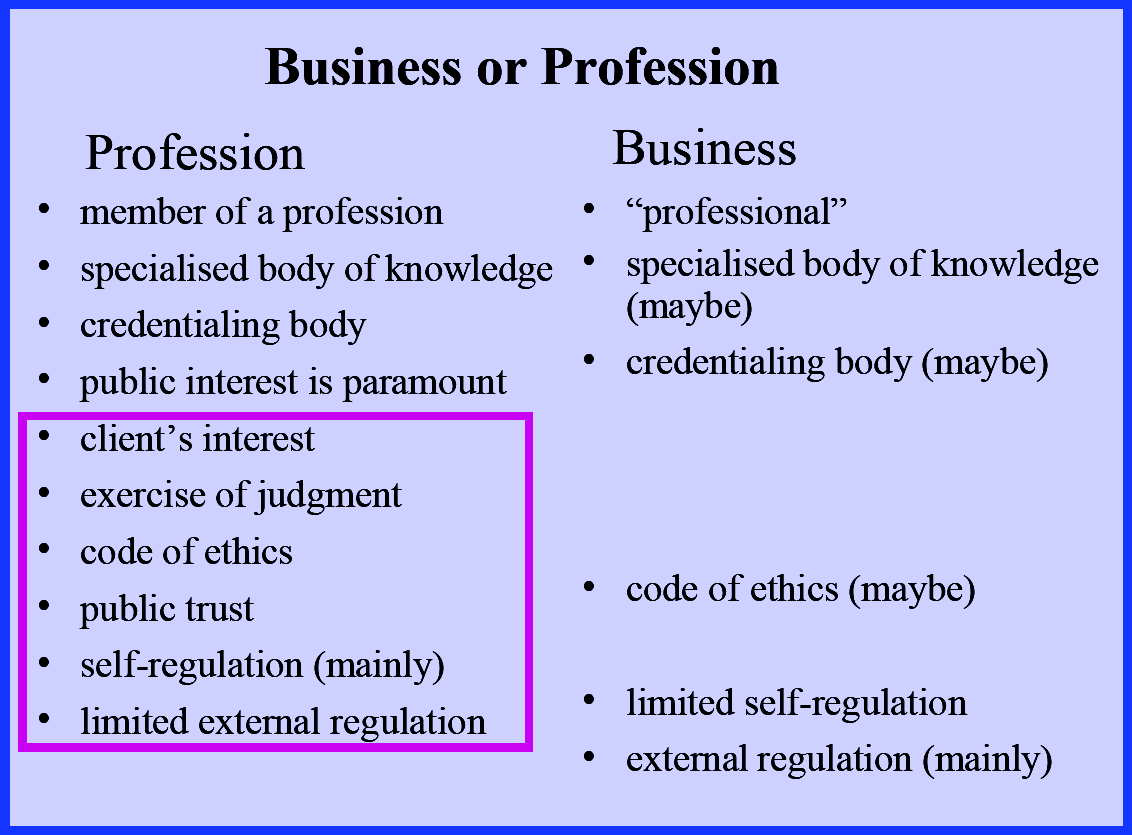

Cohen then talks about business and the profession.

The big difference between profession and business is profession have this extra bit about the public interest and the client interest. They have a duty to survey the whole landscape and do what is best. Professions and professionals must do that stuff as above. You can't be a profession if you have some extra incentive (eg. being paid to do something against the client and public's interest).

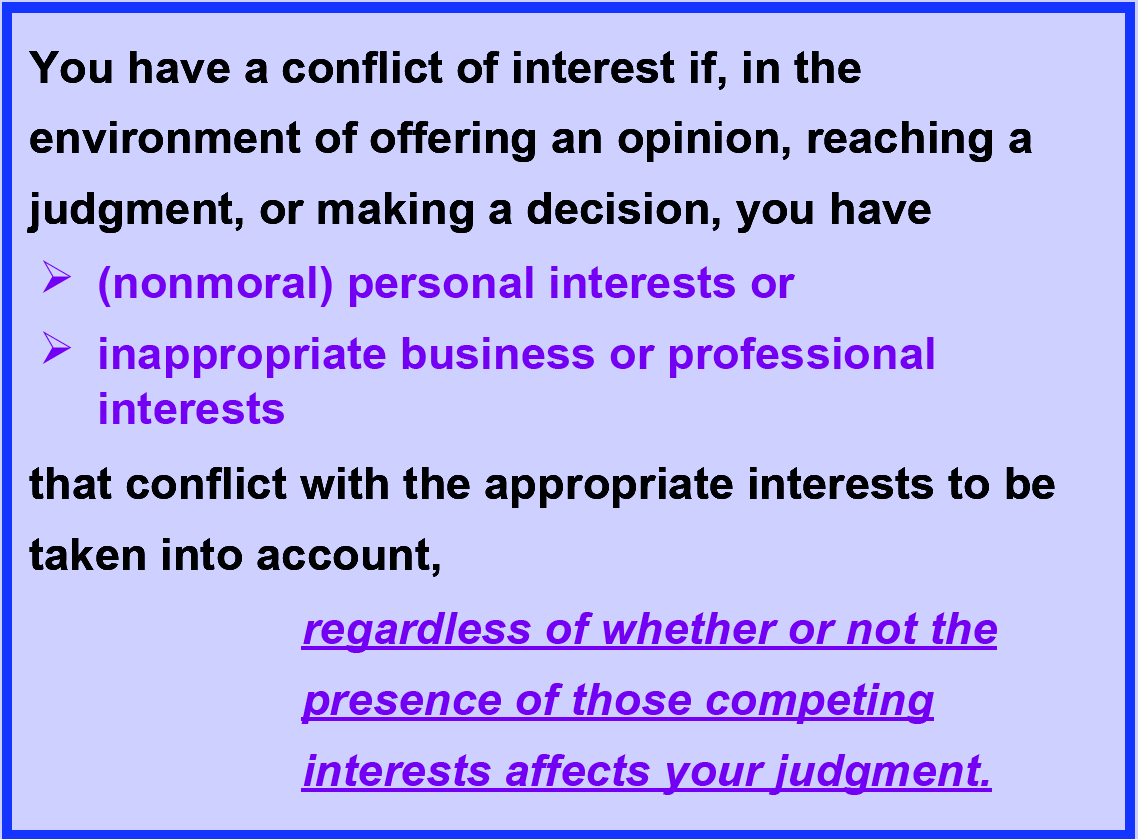

"A person’s having a conflict of interest is not the same thing as a person’s being affected by a conflict of interest." People who say they don't have a conflict of interest just because they are not affected by (or more specifically their judgement is not affected by) a conflict of interest doesn't mean they don't have a conflict of interest.

Two more good slides. This first one shows two organisational models, one where the top has great power, with this comes great responsibility, the other where they all have power, with this comes great trust.

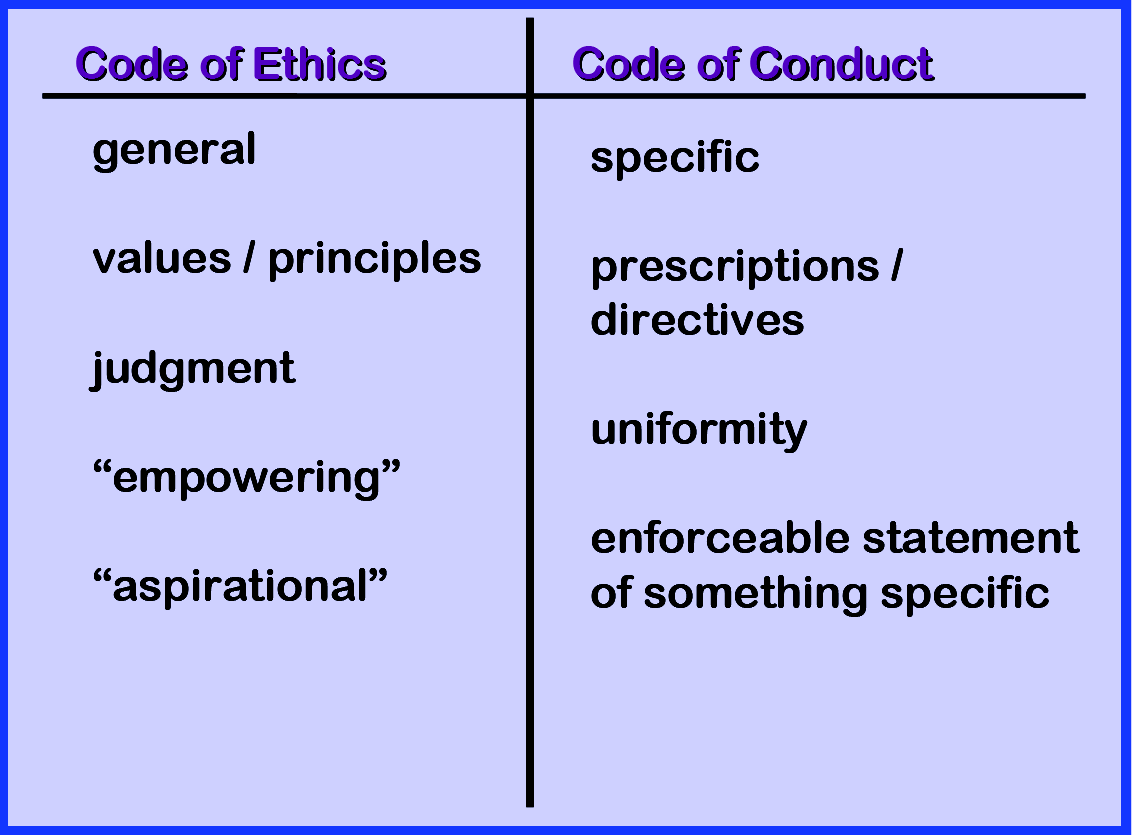

The second shows some of the modern differences between a Code of Ethics and a Code of Conduct.

Any principle/value will require judgement. Say you subscribe to the principle of honesty. At some stage you will need to make a judgement based on this principle. For example (and Cohen makes the story sound more convincing than I do here) you are at home with your close friend, Bob. Bob says he is scared as some crazy person is out to get him. Someone then knocks on your door, you answer and there is a big strong man there with a knife in his hand who asks is Bob here. Honesty does not require that you say yes he is here. You make a judgement on the principle/value, and in this respect Code's of Ethics are empowering.

Code's of Conduct are different. They are not for introducing new values. They are there to remove judgement. They tell you exactly what to do in specific situations. One area they may deal with is gifts/bribes. They may say that you cannot accept any gift you receive over a given about. They take the heat off.

Although Cohen did not cover this in the lecture, the lecture slides from last year looked into management and leadership issues and ways to promote ethical behaviour in an organisation. I find this interesting so I'll go over a couple of these things here.

- Leadership involves authorising and empowering others to behave ethically.

- People are more likely to behave ethically when:

- managers behave ethically

- organisational values are clear

- ethical behaviour is rewarded

- sanctions for unethical behaviour are clear

- there is practical ethics training

One last thing about morals and ethics. Back in COMP1917 Richard Buckland made a good statement he said something along the lines of come up with your own ethics and moral beliefs, and stick to them. I think this is good advice.

Also here are some notes made by the COMP1917 class which seem relevant.

- "Ethics is the way you behave when people are not around and there is a spanking new Alienware laptop sitting on the table in front of you waiting for you to steal.

- When you face ethical dilemmas at work, don't forget you can ask other professionals from your field for advice on how to handle such situations.

- Discussed a large range of examples of ethical dilemmas and scenarios which present interesting problems:

- Hitler's guards - Each of Hitler's guards, when told to throw the next lot of prisoners into the gas chambers must have each thought inside that they didn't want to do it, but nobody had the courage to say anything. Maybe if one guard refused, all the others would, then a message might get sent that what they were doing was wrong.

- Richard's friends - was put on the spot by her boss in an interview with a client to lie about the progress of her software. In spur of the moment she lied and ever since the boss does it regularly now. She feels like she is doing the wrong thing and doesn't know what to do.

- Richard's advice on ethics was for each person to sit down and work out exactly what they think is ethically wrong and ethically right, and then never break that. It doesn't matter what he thinks, in the end it's YOUR ethics and morals that count for yourself. He said that breaking morals breaks the spirit and that we get extreme happiness from obeying our morals and doing the right thing. He also said we need to plan ahead, and attempt to predict ethical dilemmas before they arise, that way we can think about them and make a proper decision, since during the heat of the moment we will often give into temptation and fail miserably.

- Whistleblowing - extremely difficult thing to do, the company/government will attempt to discredit your character and make a mess of your image etc. If anyone feels like whistleblowing read a book called "the Whistleblowers Handbook" by Brian Martin. Richard says its a great read."-- COMP1917 08s1 Class.

References:

Cohen, Stephen. 2009s1 SENG4921 Lecture. Audio. 2008 Slides.